Consonants: problems or opportunities

How do they cause problems? Consonants can be challenging because they alter or interrupt the flow of air and vocal tone, which presents the need to coordinate things so the consonant doesn’t misadjust the registration and/or resonance.

Singers are often tempted to solve this by pronouncing very weak consonants or leaving them out altogether. This, of course, makes the words of a song incomprehensible. As any choral director knows, singers need, in fact, to exaggerate their consonants just to make them audible because performance spaces can be full of echoes, other musical parts are happening simultaneously and words, in the context of singing, can be difficult to understand in the first place.

As a general principle, coordinating consonants with the vocal tone means giving every vowel and consonant a sufficient amount of time. Take the word “flight”, which contains the following sounds:

- “F” is a non-voiced sound made by air movement between the bottom lip and the top teeth.

- “L” is a voiced sound made by singing with the tongue in contact with the roof of the mouth.

- The vowel “I” is actually a diphthong, meaning it has two sounds, namely “ah” followed by “ee”.

- The “T” sound at the end is produced by completely blocking the mouth with the tongue, building up air pressure behind it and then releasing the tongue suddenly.

You can see that a simple little one-syllable word like flight can present challenges: You need to stop phonating but keep air flowing for the “F”, restart phonating and sing through the “L”, pronounce two distinct vowels (even though you only see one written) and finish by stopping the air flow to end with a little mini explosion of the tongue for the “T”.

When pronouncing distinct and audible consonants, we are encouraged to exaggerate them because, even if it feels contrived and silly to do so, in reality it doesn’t sound that way to the audience.

There is a danger in how exaggerating consonants can lead to trying to simply use more force to do it. This works for the plosive consonants like “P” and “D”, but the liquid consonants like “L” and “F” mostly just need enough time to be audible. I should mention that the same is true for the diphthong vowels, as in the word “flight” discussed above.

You will need to work out how to fit all these sounds into the musical line, giving each one sufficient time and energy to be audible. Allotting sufficient time to each and every sound will help mitigate any sense of effort or strain arising from crisp and clear enunciation. With practice, this gets easier and becomes a habit.

Rapid words can be a chance to demonstrate your vocal virtuosity. It takes energy to declaim a lot of words in a short space of time, but remember that it’s more about timing and coordination than it is about force.

Perhaps this gives you a new appreciation for physical processes you execute without paying any attention to them every time you talk!

Types of consonants:

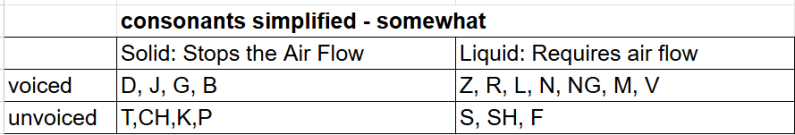

If you do an internet search on the types of consonants you will get lots of ideas on how to classify and think of how we produce them. For the sake of simplicity and relevance to the singer, I have arranged them into a matrix with 2 dimensions:

- Consonants that are either voiced or unvoiced

- Consonants that are liquid (they use air flow) or solid (they stop air flow)

The reason I divide them up in this way is because these 2 intersecting dimensions give us the main issues that a singer needs to solve when singing consonants, namely:

- For voiced/liquid consonants, you need to keep the tone going while you pronounce the consonant with your mouth, giving it enough time to be audible. For example, "Alleluia" has those liquid "L" sounds where the tone keeps going. For them to be audible, you just need to spend time on them.

For the other 3 types, you need to interrupt the tone to pronounce the consonant:

- unvoiced/solid consonants restart the tone after the “plosive” burst of air.

- unvoiced/liquid consonants similarly restart the tone after but there’s no need to stop the air flow to build up pressure for a plosive burst.

- voiced/solid consonants restart the tone simultaneously with the plosive. This is challenging to execute in singing, but also presents an opportunity for voice training.

Starting (or restarting) the tone is called the “vocal attack” or “vocal onset”. The attack sets up the voice for the following note or phrase. See the next article for how you can use consonants to improve your attack and your vocal tone.

Add comment

Comments